Cloud/Paper/Screen (218 Photographs of Clouds in the George Eastman Museum Collection, 1850-2006), 2020

54:34 min. digital video loop; no sound; 3.81GB; 4K - 2840x2160 res., digital images of paper photographs from the GEM collection. I created dissolves between each cloud image so that no image is fully viewable without another overlaid. The resulting clouds are hybrids; morphing into one another. In this work, not only does the reflective light of the paper substrate become projective light on the screen; the flatness of screen-space compresses paper, air, and screen. I created a new compressed cloud-scape where cloud, scratches, fingerprints, smudges, dust, decay, and screen are one and the same. Sometimes you can’t tell what’s what. And really this video is only possible because of the abstract nature of cloud forms to begin with.

Cloud/Paper/Screen (218 Photographs of Clouds in the George Eastman Museum Collection, 1850-2006), 2020, single-channel digital video, 5:00 min excerpt from 54:34 min

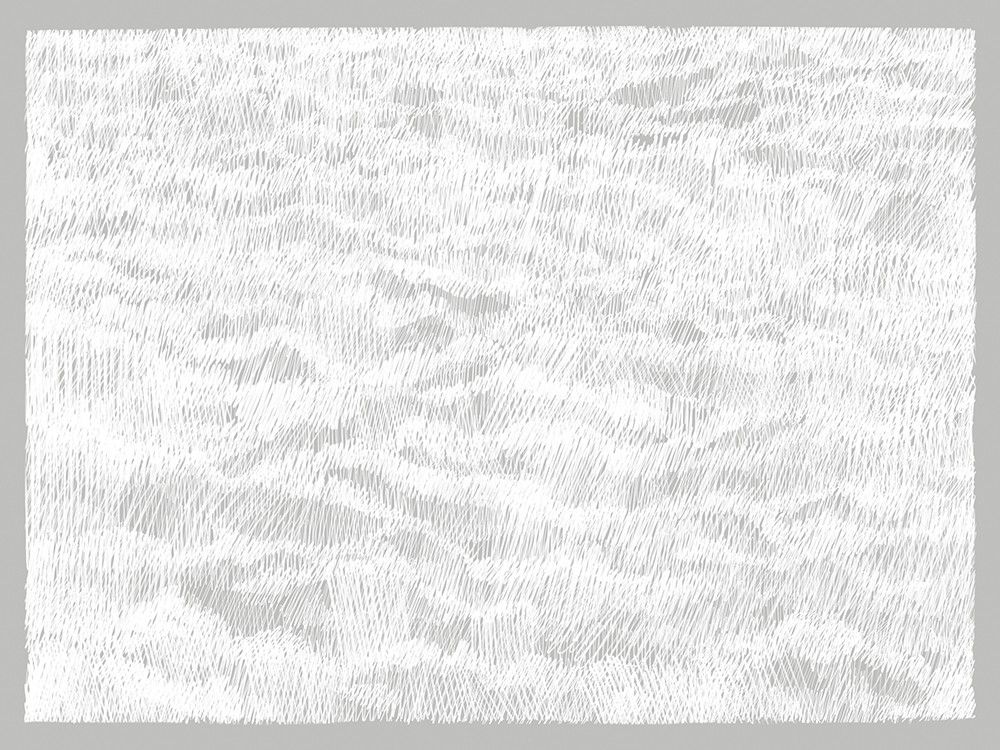

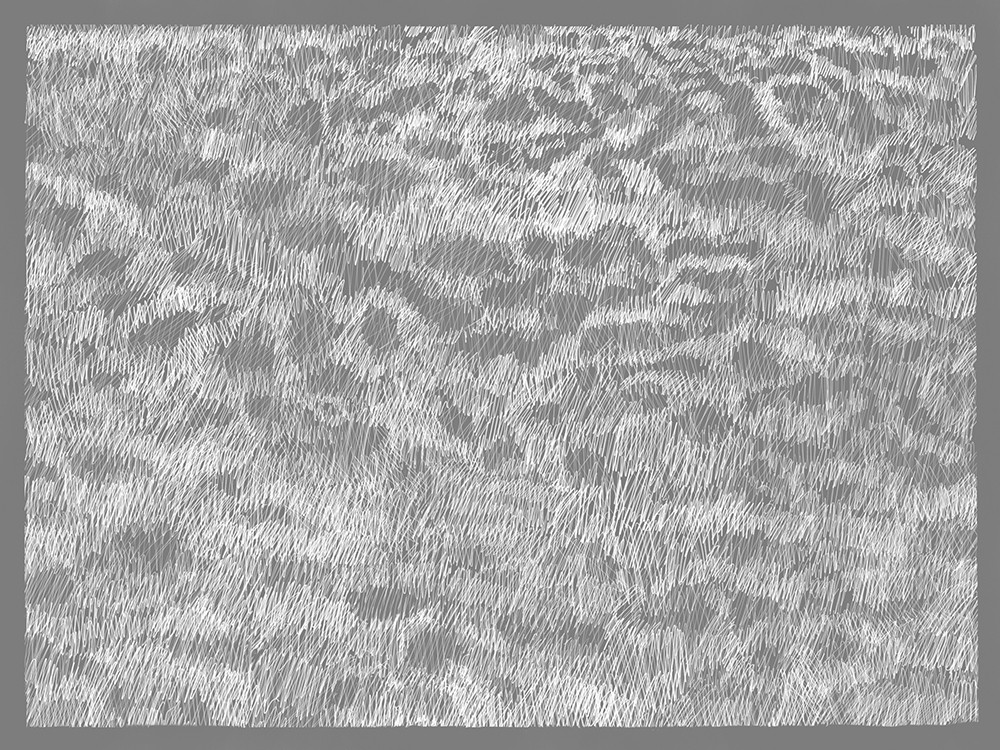

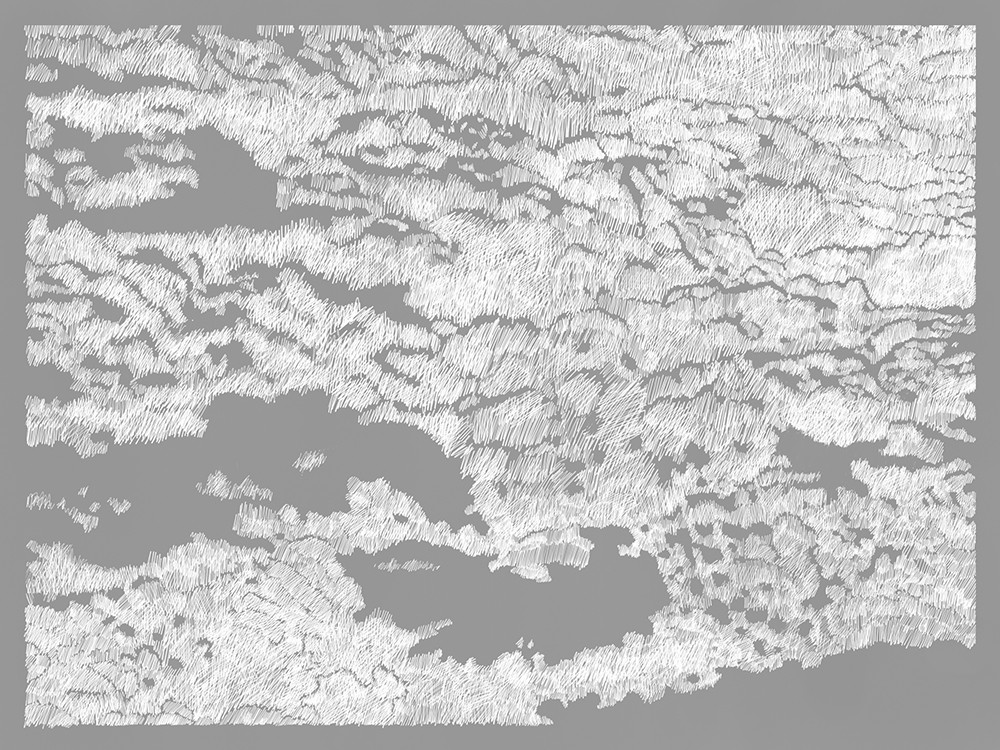

Cloud Inversion, 2019, comprises printed iPad drawings based on pictures I took with my iPhone of clouds from airplane windows as I traveled. On my iPad I used an opaque white “marker” tool to draw over the dark areas of the image (white, being the most opaque pigment, is the best at blocking light - so on screen, white = dark). I then removed the photograph underneath… basically inverting the image (and the cloud).

Cloud Inversion, 2019, 20 - 7.5” x 10” archival pigment prints on Hahnemuhle Rag paper. Installation at George Eastman Museum, 2020.

Cloud Inversion, 2019

Cloud Inversion, 2019

Cloud Inversion, 2019

171 Clouds from the V&A Online Catalog 1630-2018; 2018, commission for V&A media wall; digital video; approx. 60min loop; 171 Clouds… comprises images of clouds cropped from the photographs of landscape paintings in the digital archives of the V&A. I created dissolves between each cloud image so that no image is fully viewable without another overlaid. The resulting clouds are hybrids; morphing into one another, at times seeming completely abstract and ephemeral and at other times indisputably derived from online digital photographs of material paint on canvas. Cropping the clouds from these photographs of paintings, I focus on those that are the most “cloud” like, painterly and fluffy. They could be the sort of image taken by someone out of an airplane window.

171 Clouds from the V&A Online Catalog 1630-2018, 2018, single-channel digital video, 1:55 min excerpt from 56:00 min

From an interview with Kati Price, 2018

For the opening of our new Photography Centre, American artist Penelope Umbrico has created 171 Clouds from the V&A Online Collection, 1630-1885. Umbrico works mostly with images she finds on the internet, presenting them in ways that reveal the fluidity of digital photography. For this video commission, she sifted through the V&A paintings collection online and extracted details of clouds. The work explores the transition from fleeting clouds to material paint, and then from digital code to physical screen. Here, we ask her a few questions about this commission.

Can you describe the piece?

It’s a digital video comprising images of clouds cropped from the documentation photographs of landscape paintings that I found in the online database of the V&A painting collection.

Why clouds?

Since this piece was commissioned for the screen, I wanted to make a work about the ephemerality of digital images in relation to the materiality of the screen. The idea of vaporous clouds rendered in the material pigment of paint seemed to be an ideal analogy. It’s a paradoxical undertaking to render a cloud, abstract and with no surface, with the physical materiality of paint.

Can this piece be considered as photography? How does it speak to photography and photographic practice?

Well, yes, because what we are looking at here are not paintings of clouds, but photographs of paintings of clouds. When I discovered the V&A online database of its paintings, I was struck by the fact that I was looking at photographs, not paintings – the photograph is the ultimate medium to hide its own materiality. I think this is something we don’t often think about when we look at photographs – that first and foremost we are looking at a material object. And in this case, I was looking at these photographs of paintings on a screen, an equally material object. Though we tend to think of these mediums as invisible, they are still there affecting us in multiple ways – we learn of the world through their surfaces, they filter almost everything we see. I’ve been thinking of these clouds in a similar way – like a screen or a photograph, cloud effects are often unseen but they are felt. They are our background, our mood, they inform us, and affect us in ways we are often not consciously aware of.

Can you explain more about the process of making this piece? How did you work with the V&A painting collections?

In collecting the images from the V&A database, I focused on those landscape paintings that had the most iconic clouds. I cropped those clouds very closely so that they could look like the sort of image taken out of an airplane window. I was thinking about the fact that on the web all images can be blended and mixed with all the other images (something you can’t do with physical paintings). I wanted the clouds to dissolve into one another, to become indistinguishable from one another, so I imported them all into video authoring software and applied slow dissolves between each image so that no image is fully viewable without another overlaid. And I wanted to speak to the filtering properties of clouds as an analogy to the filtering properties of photographs and screens, so I applied the video authoring software’s pre-set ‘colorizing’ filters, weaving them in and out.

The resulting pixelated clouds morph into one another, at times seeming completely abstract and ephemeral and at other times indisputably derived from online digital photographs of paint on canvas.

I like the idea of the dreamy, ungrounded-ness we associate with clouds seen within the equally dreamy ungrounded-ness of digital space, and yet contained within the physically claustrophobic space of a thin flat media screen mounted on a wall.

What might this piece tell us about the future of photography and photographic practice?

Not sure about the future of photography, but I think of this piece as an analogy to the current state of photography. Like the cloud, photography on the web is inherently fragmented, un-assignable, un-locatable, indeterminate, de-contextualized, and constantly changing. But when printed, photographs are a reflective medium like the painted clouds in the photographs of them that I am using. I am thinking about the technological history of representational media from opaque to transparent, visible to invisible, reflective to projective… and what it means to see images that were made to reflect light (paint on canvas, ink on paper) within a projective medium such as the screen.

This work articulates the translation from projective to reflective to projective again: the original cloud, painted, then photographed, then digitised, digitally uploaded (to ‘the cloud’), downloaded, digitally filtered and re-authored, and re-presented here on a flat media screen. The process returns the cloud to its projective nature: both screen and cloud filter projected light. But I am interested, here, in the fact that filtered sunlight is replaced by the filtered electronic light of the screen. So perhaps this is not an analogy of the current state of photography, but rather, it might be the current state. And I wonder what affect that has on us.